Message in Edith Wharton's Garden & Tips For Your Own Literary Pilgrimage

Real Writing in the World #10: Literary Pilgrimage (Part II)

Two 80-year-old parents with COVID (and then one of them having a surgery) later, I’m finally sharing this post!

Welcome! This newsletter celebrates Real Writers and their dreams through creative play, writing life adventures, honoring cycles and seasons, and inspiring writing/editing tips.

If you haven’t read the previous post about my private writing session in Emily Dickinson’s bedroom, it’s part one of brief literary pilgrimage I made in October. Read it here. Check out the other Real Writing in the World writing adventures and subscribe and enjoy ways to bring your writing life to life beyond the page or laptop!

The drive to Edith Wharton’s home, The Mount, was on another atmospheric fall day of intense reds, golds, and oranges, a spectacular mix of gray and blue clouds, and the swish and scratch of leaves. The road wound through quaint little towns I wanted to move to immediately, where I would help save my family’s failing business, get roped into managing a harvest festival, wear cozy sweaters and a different coat every day, drink hot chocolate overflowing with whipped cream and marshmallows without getting a stomach ache, reunite with old friends, wake up with perfect hair, and discover the life I wanted was there all along.

Okay, that’s a Hallmark movie, but these towns cast a serious spell in the fall.

The walk from the parking lot was through woods with art installations scattered throughout, creating much anticipation about the first glimpse of the house (like Elizabeth Bennet seeing Pemberley in Pride & Prejudice).

Edith Wharton and Emily Dickinson were different writers but both prolific. What struck me immediately upon see the house is the obvious difference—Edith was a very successful writer, making a large income from her writing.

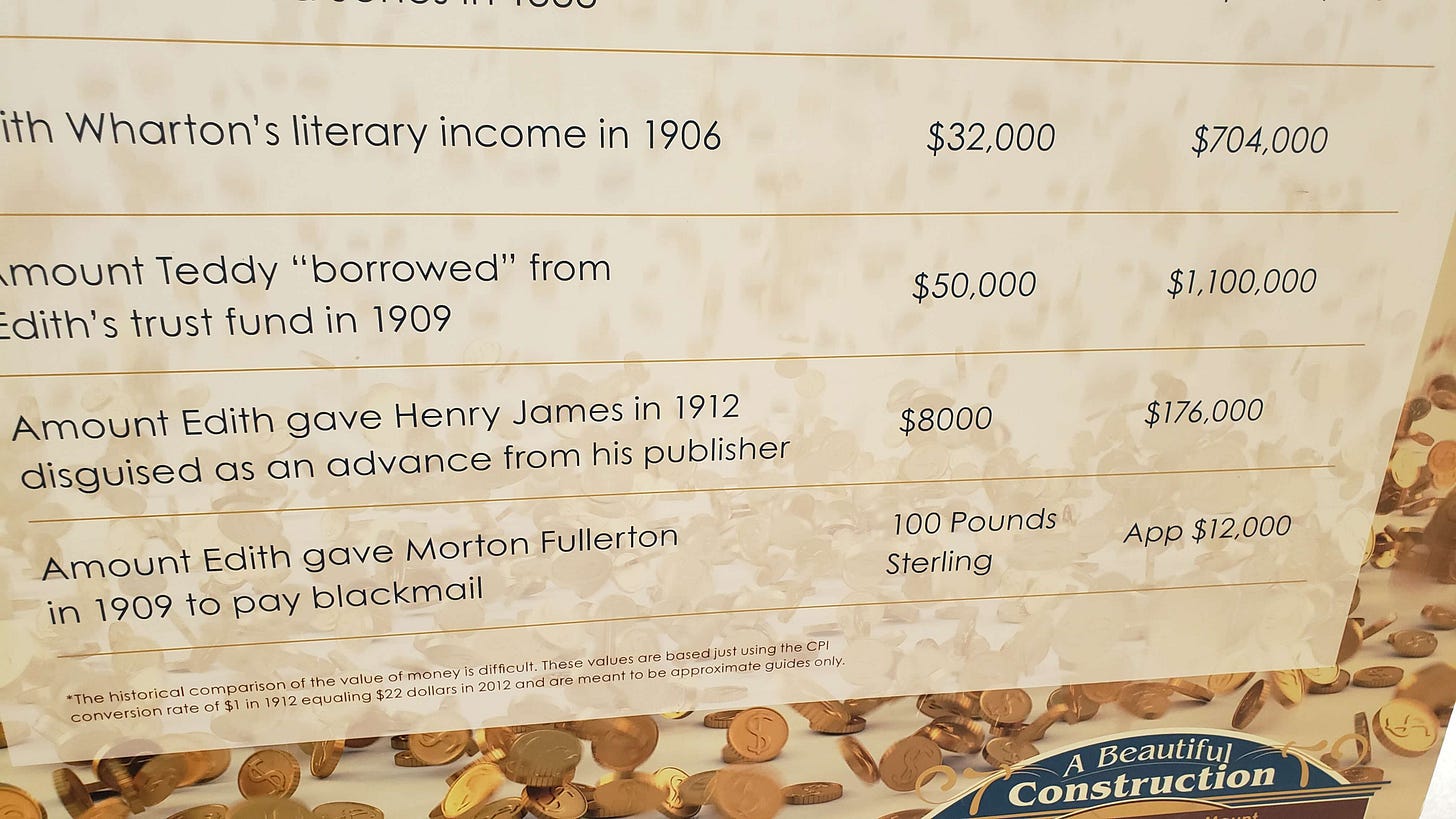

Between interest from her father’s trust fund and an inheritance from a cousin, she had $130,000 (equivalent to $2.8 million today). Her literary income in 1906 was $32,000 ($704,000 today). She’d have to be making a good income to have her husband “borrow” almost half of her family money to set up his mistress in an apartment in Boston… The blackmail was paid to journalist Morton Fullerton, with whom she had an affair.

She also was the first women to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1921 called the Novel Prize then for The Age of Innocence in the 4th year of the prize’s existence.

Because she was a woman there was controversy about it and a juror noted they had not awarded it to her, but Sinclair Lewis. The Pulitzer board overturned the jury’s decision.

Dickinson and Wharton both had their literary friendships. What draws me to Wharton, more than her writing (it’s hard to stomach main characters Lily Barth (The House of Mirth, 1905) and Undine Spragg (The Custom of the Country, 1913), but The Age of Innocence, 1920, makes up for them both), is her close friendship with Henry James, one of my favorite, favorite writers (The Ambassadors had a profound effect on me, one of those “right book, right moment” things).

James was a complicated person who dove deep into the psychological in so many amazing stories (you either like him or you don’t; no worries if you don’t) that have resulted in countless film adaptations. If you don’t know that you know James: The Portrait of a Lady, The Golden Bowl, The Wings of the Dove, Daisy Miller, The Turn of the Screw, and more.

James stayed at The Mount many times and had his own bedroom, which was not decorated, but it was still special to stand in that space. The dining room was set with places for Edith’s close friends, including James. I was excited to walk the rooms and grounds he’d visited and my admiration of her grew during my time there, though she was also complicated (as we all are). She was born Edith Newbold Jones into high society and affluent wealth (her family was said to be the inspiration for the saying “keeping up with the Joneses”), was a fierce imperialist who opposed women’s suffrage, but also aided refugees in WWI, housed 600 war orphans, opened a tuberculosis hospital, and created jobs for women via sewing rooms.

We like to think that people we admire for their art, or whatever it is that attracts us, make decisions and have beliefs we agree with, but that isn’t the case. They are human.

The house with its French, English, and Italian influences is incredible, regal, classic, but warm, and worth a visit for the few rooms that are decorated. There are some of her personal belongings, but the space is mostly a museum telling Wharton’s story through text and images sharing her history, writing, friendships, romantic alliances, philanthropy, and life. The gardens are just plain gorgeous, with the Italian garden my favorite.

The house felt created by love—you could feel how much Wharton invested herself in its design.

Edith Wharton lived at The Mount for about ten years, during which her marriage ended, in part due to the mental deterioration of her husband, Teddy (he suffered from bipolar disorder), his affair, her affair. After their divorce, she moved to France in 1914 and lived there until her death from a stroke in 1937.

It was still a compelling experience to wander through the undecorated rooms. In a basket in one were calling cards (in French) for visitors to fill out and leave, which I did, and took an extra one as a memento.

It’s a very worthwhile place to visit and despite its size, feels welcoming and personal to her. She was very much into architecture and décor and designed the house, and wrote a book with her architect. The gardens are lovely—there is a beautiful passage called the Lime Walk that connects the French garden to the sunken Italian gardens. Check them out on the Wharton site.

I took so many pictures that my phone died early on and I didn’t have time to walk back to the car to charge it. There was a bus tour coming and the house was scheduled to close at 1 p.m. and the gardens at 2 p.m. I wandered through the rest of the garden and through some paths in the woods without my phone (like the old days—not experiencing something through a filter). One path warned me to watch out for bears, which was a bit of a shock—I hadn’t expected that and didn’t encounter any.

In the Italian gardens I plucked one tiny, long-dried flower to press in my notebook. At the end of the path I found this quote carved into stone and copied it onto the back of the calling card with my “creative and courageous” pencil from the writing session in Emily Dickinson’s bedroom the day before:

“In spite of illness, in spite even of the archenemy sorrow, one can remain alive long past the usual date of disintegration if one is unafraid of change, insatiable in intellectual curiosity, interested in big things, and happy in small ways.”

— Edith Wharton

I’d read this quote a long time ago and forgotten about it. It found me again at the right time. What better advice for midlife?

I walked down the lawn toward Laurel Lake and entered a fairy woods of old trees, a bubbling, rocky stream, mosses, and makeshift bridges to cross. One was pure art—newly fashioned as the wood glowed with youth. Its strands had been bent and curled into overlapping half-circles and I stood on it watching the water flowing down through some rocks, under the bridge, and on into the woods, catching leaves and acorn caps and bits of pine cones to carry until they lodged between sticks or rocks.

It felt something was needed to mark the moment—not just the visit, but the trip itself, the time in Dickinson’s bedroom, my respect for the independence and writing of both women, maybe even a promise to myself.

Spontaneously, I took out the flower and the calling card and read the quote three times (three is a magic number and once wasn’t enough), as a kind of promise to myself, then tossed the flower into the water, watching it spin and swoop away.

I followed the path that seemed to circle the lake, plunging me into dense trees, bushes, tall, dried grasses until the ground muddied significantly and I stopped at a narrow track that intersected two sides of the pond, unsure of whether or not it was solid.

While I stood there, soaking in the harvest colors of autumn, not gilded by sun or masked by shadow, but clear, sharp, and deep—the silver water, the rust and crimson leaves, the pine trees and the gray-blue clouds—the quiet was interrupted by a pair of geese soaring overhead at top speed, their honking loud and urgent, splash-landing with so much noise and heart-pounding drama I actually gasped and I had to laugh at myself as I walked back to the house. It was time to go.

I made a real effort on the trip to not look for signs and symbols in everything. It’s why I wrote about the experience of being in Dickinson’s bedroom rather than turning it into a poem or regular writing session (it was not a regular writing session), or grand meaning. And visiting The Mount was a place to drift through for pleasure, without purpose except to visit Wharton and James.

Sometimes the world just is. We can describe it. Feel it. Inhabit it. Observe it. Merge with it. But to search for meaning and metaphor in everything is not truly experiencing, connecting, accepting the reality, cycle, the change, the loss, the surprise, as it is—part of the wheel turning, in the way it turns just for me, which is different from how it turns for a friend, a coworker, a stranger on the street, or you, Real Writer.

I find the more I seek out the seasons, whether they are literally seasons, or the ones we pass through in our lives, sit with or inside them, and not try to make anything of them but what they are, I feel more grounded, less anxious, less lost. More accepting or maybe a better word is accepted.

The seven-hour drive home was full of gloom, rain, fog (wonderful), and I spent it listening to readings of Wharton’s ghost stories, then Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw. You can listen to some of Wharton’s ghost stories here —Tony Walker’s Classic Ghost Stories is on Substack.

It was a perfect few days away from myself but with myself. A peek into the world outside the trenches we all dig for ourselves in life and a gentle examination of what is of value to me now, as I approach sixty. A literary pilgrimage to visit with the writers you love and admire, whose stories and poems, essays and plays, resonate with and speak to you, that light up your imagination, is not just a good idea for a getaway or vacation, it’s a chance to tune into that writer’s story of living and yours as well.

Your turn: let’s plan your literary pilgrimage

Here are some tips questions to help you decide the who/what/when/where/why of your trip. The great news is that you can’t get this wrong!

Who is your favorite author or what is your favorite book? If you have several favorites, which are you most passionate about?

Where is the magic for you?

Do you want to visit a place special to the author (home town where whey were born/grew up, where they wrote, their grave)?

Or do you want to see places from their stories? This can include places designed to give you an immersive experience (theme park, video games, virtual reality)?

What types of tours can you take? Or perhaps a writing workshop?

Is there a special event you could attend focused on them or their work?

Once you know where your Reader Heart is pulling you, go online and research your dream trip. Do not think about time or money. Pretend there are no limitations.

Don’t get practical until you’ve completed this step! Then look at cost, how much travel is involved, how much vacation time you would need. Perhaps it’s more economical to take a tour where all fees and arrangements are built in and you can geek out with other fans.

Then start saving so you can do your pilgrimage right, wringing every bit of joy and excitement out of it.

In the meantime, you can start the fun now: is there anything in your city/state or within driving distance/a train ride that is related to this author or their books?

Perhaps there’s a conference or a Meet Up group (if not, start that group and meet people who might like to join you on that trip).

Are there online events (lectures, video tours of the places you’d like to see, readings of the works) you could enjoy now?

If this feels too ambitious (especially if a trip abroad is required), chose a book or author in a nearby state or country, depending on where you live—one that enables you to make a day trip of it. Aside from gas or train fare, lunch, and whatever you spend in the gift shop (which is where I always get into trouble), it’s much easier on your budget. You’ll also practice on a trip that isn’t your dream trip, discovering what elements of the experience are most important to you.

Take pictures and have a notebook and pen with you (leave your laptop at home). Take time to write down some notes about the experience and ideas, images, sensory details, etc. that come to you. You can also voice record them on your phone.

My only don’t is: Don’t spend so much time on writing or taking pictures that you aren’t present and aren’t having the experience. If you feel capturing notes and photos will inhibit that, don’t. On a trip to Amsterdam a few years ago, I went to the Anne Frank House and could not do anything but walk through it several times, reading everything in the exhibit of her diaries, too emotional and overwhelmed. When I left, the bells of the church next door were ringing, which Anne would have heard each day, and when I went in an organ concert was just starting. The intense, soaring, layered sounds seemed like the only thing big enough to express how I felt. I stayed the entire concert and then decided to walk back to my hotel rather than take the tram. I wandered all over the city for hours and this is the most I’ve ever written about it.

Where have you gone to commune with a favorite author or book? Where would you like to go? Let me know in the comments!

Happy pilgrimage,

Chris

Wow. That house was BEAUTIFUL! It sounds like you had a great experience.